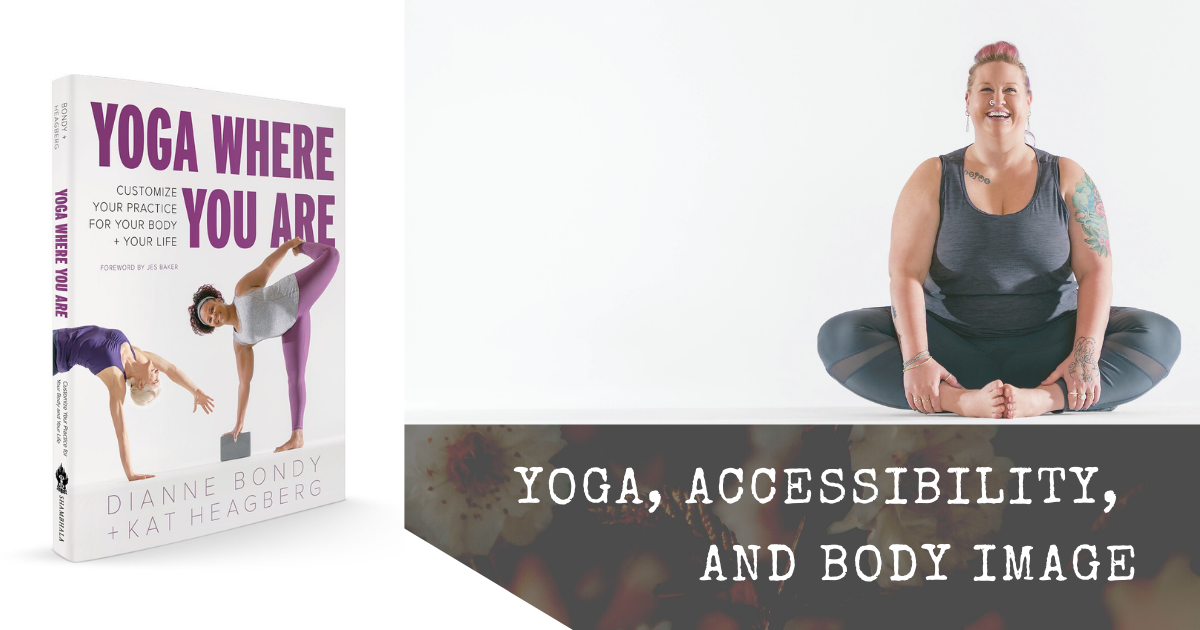

Yoga, Accessibility, and Body Image: Excerpt From Yoga Where You Are: Customize Your Practice for Your Body and Your Life

January 8, 2021

From Yoga Where You Are: Customize Your Practice for Your Body and Your Life © 2020 by Dianne Bondy and Kat Heagberg. All photos by Andrea Killam. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO. [[pg. 11-16]] Ch. 2

Yoga, Accessibility, and Body Image

The body is political. Our bodies are the only vehicles we have in which to access the world. The way our bodies look often determines the type of treatment we receive or the access we have. In Western culture, able bodies, white bodies, and thin bodies have more access to resources than bodies that don’t share those same characteristics. Bodies that are considered conventionally attractive have something called “beauty currency.”

Regardless of your gender, looking the way that society deems “beautiful” opens many doors and provides greater access to resources. Not all of us receive the same access to justice, equity, and resources such as healthcare and the distribution of wealth. Our bodies come at a price. In a white-dominated culture, people of color are forced to continually prove their worth. Individuals on the fringe of what is considered conventionally beautiful must fight to be recognized for their humanity, experiences, and expertise. Skin color, disability, age, and size all factor heavily into how society perceives each of us.

Self-doubt is largely a by-product of cultural conditioning. For people of color and people who don’t conform to societal and cultural norms, feelings of self-doubt and inadequacy become internalized. These messages of inferiority that we begin to feed ourselves are called “internalized oppression.” Mainstream culture lays out the guidelines of what is “normal” or what is “desirable,” and this keeps marginalized groups from rising to our real potential. There are structural barriers in place that keep certain populations at a disadvantage. When we look at North America today, we can no longer dismiss structural racism, sexism, ageism, ableism, fat phobia, homophobia, and transphobia. Depending on the body you are in, your access to a safe and successful life may be in jeopardy. Why do the differences between our bodies create a divide?

DIANNE: Speaking from my own experience, my fat black body comes with its own set of challenges. As a woman of color, my body is highly politicized and criticized. My skin tone and the length and texture of my hair play a major role in how I am perceived in the world. The darker I am, the less desirable, educated, or conventionally beautiful I am perceived to be, and the less bank- able or salable power I have in the world. I once had a boss tell me he found me attractive because my features seemed more Caucasian. I quit my job the next day. Society has tried to tell me that my body is worth less than those of my white counterparts. Globally, this idea is reinforced. I don’t receive the same access to justice or health care as my white counterparts. Police brutality toward brown and black bodies often doesn’t receive adequate acknowledgment or punishment, as we have seen in the cases of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, and Sandra Bland. Women of color, particularly black women, are more likely to die in childbirth no matter their education or socioeconomic background, as documented by research at Harvard and illustrated by the near-death experience of Serena Williams after the birth of her daughter.

Some questions for self-reflection and self-study to help us better define our humanity are: Why are white bodies considered to be worth more than nonwhite bodies, white male bodies worth more than female bodies, thin bodies worth more than fat bodies? Why are able bodies worth more than bodies with disabilities? Why are conforming bodies worth more than nonconforming bodies? These are the questions that can help us to better understand our humanity. These dichotomies create an “us versus them” paradigm. What, and who, do these polarities serve?

It would be nice to believe that all bodies are deemed intrinsically equal in our society, but it is simply not the case. We believe that all bodies are beautiful. All bodies are worthy. All bodies deserve our love, and respect, and care, regardless of their color, size, ability, or gender. We must begin to release our attachment to our cultural definitions of beauty and perfection, and we must begin to cherish and celebrate all of our bodies as they are.

The yogic principle of ahimsa or “non-harming” can inspire us to stop our hatred toward different bodies—including our own. Our hostility toward ourselves also creates hostilities toward each other. Our attachment to our ego and defining who we are in terms of the dominant paradigms of society and culture can keep us from exploring our true bias and prejudices.

Negative body image directly affects how we show up in the world. If we are consumed in our own self-hate, we cannot look at the world at large. We cannot advocate for ourselves or others when we are too busy hating on our bodies. The capitalist world banks on this inner conflict. It fuels our dissatisfaction under the guise of improvement: do better, be better, and buy this to help you do it.

But the inverse is also true: accepting ourselves helps us be better at accepting others. Positive body image also directly affects how we show up in the world. We do not need to buy into beauty standards that feed consumerism. We can celebrate our own beauty and the beauty of the lives that surround us.

BODY IMAGE

The term body image refers to the way we perceive our own bodies and the way we assume other people perceive us. Body image is a collection of ideas based on how we see ourselves in relationship to the outside world. Do we see ourselves as attractive, feminine, masculine, nonbinary, able-bodied, in bodies with disabilities, in older bodies, in younger bodies, in large bodies, or in small bodies? Our body image is influenced by messaging from friends, family, religion, culture, media, and society. Body image generally isn’t based in fact and can be either positive or negative.

In the second chapter of the Yoga Sutras (2:35), we are taught that settling the mind allows for hostilities to cease. We begin by ceasing hostilities toward ourselves, and then begin ceasing hostilities toward others as well. When we allow our mind to settle, we begin to disengage from the cycle of insecurities that are borne into our conscious and subconscious lives. As we learn to release our attachments to the belief that our self-worth is skin deep, we begin to recognize that our attachments to the conventional are unnecessary.

Body image is largely a product of learned conditioning. Here are some facts about body image:

» Keeping people focused on body dissatisfaction through marketing helps the cosmetic and diet industries stay profitable. By presenting a physical ideal that is difficult to both achieve and maintain, these industries are assured continual growth and profits. As noted on the Market Research blog, “The total US weight loss market grew at an estimated 4.1% in 2018, from $69.8 billion to $72.7 billion. The total market is forecast to grow 2.6% annually through 2023.”

» Washington State University found that the average size of the American woman now falls between a 16 and an 18, the lower end of plus sizes. The average size of a fashion model is 0–4.9

» The thin ideal is unachievable for most women and is likely to lead to feelings of self-devaluation, dysphoria (depression), and helplessness.

» As Mario Palmer noted, “Approximately 91% of women are unhappy with their bodies and resort to dieting to achieve their ideal body shape. Unfortunately, only 5% of women naturally possess the body type often portrayed by Americans in the media.”

» “In a survey, more than 40% of women and about 20% of men agreed they would consider cosmetic surgery in the future. The statistics remain relatively constant across gender, age, marital status, and race.”

» “Students, especially women, who consume more mainstream media, place a greater importance on sexiness and overall appearance than those who do not consume as much.”

BODY IMAGE IN YOGA

In much of the contemporary practice of yoga, diet and fitness culture cross over. Most popular yoga teachers are thin, young, able-bodied, and white. Those are the gurus and experts that are lifted to celebrity status. Why is this so? Is it because they reflect the beauty, diet, and fitness culture ideal, which we have been conditioned to accept as normal and desirable? Asking questions about why we revere a yoga teacher can be a powerful tool for both self-reflection and cultural reflection.

At its root, the asana (or physical) yoga practice is designed to promote holistic wellness, as we aim to cultivate the mind-body connection. A healthy and regular yoga practice should be viewed as a self-care practice—a safe and comfortable tool for compassionate self-study. In this view of yoga, it is impossible to ignore a direct correlation between practicing yoga and the development of one’s own body image.

Taking a closer look at the effects of yoga on body image should be a priority for everyone who practices yoga—especially teachers, both seasoned and aspiring, and people who work in yoga media. Teachers and yoga media can have a powerful impact on students’ body image—either supporting a positive view of their self-worth or reinforcing a negative body image. It is important for teachers and professionals to look at the language we use in speaking about ourselves and how we project that on to others.

For years, mainstream yoga publications, websites, and clothing companies have carefully crafted a very specific image of what yoga looks like. Pictures of thin, almost exclusively white women are disproportionately featured in the advertising and promotion of yoga. Very rarely do we see an “average” or “regular” sized person doing a simple yoga pose. Even more rarely do we see someone with a disability, men, nonbinary people, older students, or other elements of diversity.

Thin, attractive, flexible, fair-skinned women sell yoga magazines. This aesthetic was very carefully crafted as aspirational marketing. Society creates this image so that corporations can continue making money off our insecurities about ourselves and our bodies.

The notion that a “yoga body” must be young, thin, and flexible illustrates how pervasive the ideals of beauty are in our perceptions of yoga practice. Many yoga teachers come to this practice with natural flexibility and the privilege of an able body. Sometimes, however, this privilege may inadvertently affect our ability to serve students with body types that are different than our own. Due to a lack of understanding, we may feel unsure of how to modify poses for students who come to our classes with different body types and levels of ability. Yet students come to us for guidance when they are unsure how to serve themselves or adapt the practice to their bodies.

While it is not our intention to exclude students because of our own lack of understanding or unfamiliarity, it happens! When we neglect to provide an atmosphere of understanding and appreciation for different body types and abilities in our classes, we can cause students to feel marginalized and alienated from the asana practice. In this way, we can leave students feeling as though they are unable to execute or experiment with a particular posture, or worse, we can leave them feeling as though the entire asana practice and all its benefits are beyond their reach. Sadly, this then creates the internal message that there is something “wrong” with the student’s body, and thus perpetuates negative impressions, thoughts, feelings, and opinions.

We firmly believe that all bodies are yoga bodies.

In actuality, it is not the student’s body that needs adjusting in a pose, but rather the asana or posture itself that requires an adjustment or the use of a different prop for support. By adapting the posture to the student’s body, as opposed to shaping the student’s body into the posture, we as teachers can provide an atmosphere of understanding and appreciation for all bodies within our classes. As a result, we can come to serve all of our students in an effort to improve and elevate a positive and healthy lifestyle, regardless of a student’s body size or ability.

We can apply this same understanding of all bodies as yoga bodies in our own personal practice as well. The words we use to talk to ourselves have power. We don’t need to believe that we must change ourselves to fit a pose or a class or a perception of a yoga lifestyle. Instead, we can adjust a pose or a class or a lifestyle to fit us right where we are. We can meet and celebrate our own unique bodies and experiences, and we can customize our yoga practice to benefit our unique bodies, minds, and spirits.

APPRECIATING OUR BODIES

The most important step in appreciating our bodies is to meet ourselves where we are.

As yoga teachers, we can create a truly inclusive yoga class by coming to understand and appreciate different body types and abilities and by learning how to adapt a pose and a practice to fit different kinds of bodies. We can share inspiration from, and promote the work of, a diverse range of teachers. We can focus on encouraging students to come to the mat and accepting where they are in their own practice. We can recognize that some students come to the mat with a genetic privilege, and we can celebrate that all bodies are yoga bodies.

Many of these ideas also apply to our personal practice. We can work on identifying the stories we tell ourselves about our worth, power, or beauty—on and off the mat. We can begin to question the negative stories, and we can begin to celebrate where we are in our lives and in our practice, regardless of how it looks. We can look for teachers and media that highlight accessibility and acceptance. We can focus on coming to the mat for any amount of time, and we can know that we don’t need to change to find benefit.

The Health at Every Size (HAES) movement makes the powerful claim that we can be healthy people regardless of how our bodies look. Their website (www.haescommunity.com) is a wonderful resource for learning about how to respect every body, challenge our assumptions, find compassionate self-care practices, and work for justice. Other groups, such as the Yoga and Body Image Coalition, are active in trying to change the dominant narrative around yoga and health, and they also offer excellent resources.

We don’t need to overcome our bodies—we need to overcome our attachment. What if we could overcome our attachment to diet culture, the beauty industry, and celebrity culture? What might we be capable of if we began to view our bodies with satisfaction instead of distrust?

At its core, attachment is based on fear and insecurity. When you forget your true Self—which the yoga tradition tells us is pure consciousness, pure potentiality—you begin to believe that you need something outside of yourself in order to achieve happiness.

And yet, you don’t. You are worthy just as you are.

This book offers ideas for how to adapt poses to all kinds of bodies, so you can customize your practice or support your students. It also offers supportive language in talking about poses and bodies—this can shape how your talk to yourself or to your students. We hope this book can serve as a tool to help you begin to accept all bodies—your own and others.

You might consider these questions on your journey:

» The first step in accepting our bodies is letting go of our attachment to beauty and perfection as defined by our culture. What if we saw all bodies as equal regardless of color, size, and gender?» Do we see yoga as an individual pursuit or as something that fosters connection to each other?